Croatian City’s Pioneering Approach to Civic Education Catches On

Almost half of high-school students that will soon be eligible to vote don't know the definition of dictatorship or constitution, and less than half can correctly name the prime minister, who constitutes the opposition or how ministers in the government are chosen. The average number of correct answers was only nine out of from 19, and only six when it comes to students from three-year vocational high schools.

"A terrifying level of ignorance has been constant through all those years. There is a serious deficit in the democratic political culture of Croatian high-school students," says Berto Šalaj, a political scientist at the Faculty of Political Science in Zagreb, who participated in this research.

Results are equally disappointing when it comes to attitudes toward politics and institutions: around 60 per cent of pupils think that people enter political parties only to get a better job, and only 16 per cent trust the government.

Slightly improving over time are attitudes toward marginalized groups and minorities as well toward gender equality, but one-third of participants in the survey still thinks homosexuality is a disease and less than half of students oppose the idea that women are biologically predetermined for certain jobs.

Šalaj is one of many experts to blame these results in large part on the absence of proper civic education.

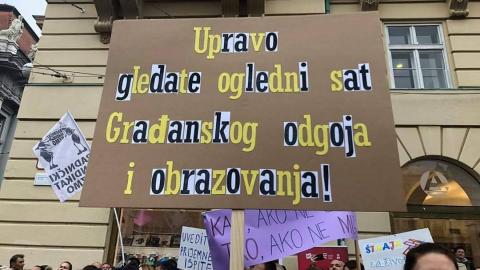

Usually defined as a set of skills, experiences and knowledge that empower students to participate in democratic processes and become active, tolerant and responsible members of the community, civic education has for years been a heavily politicized theme in Croatian public discourse.

Since the end of the 1990s a set of topics taught only optionally as a part of other subjects, civic...

- Log in to post comments